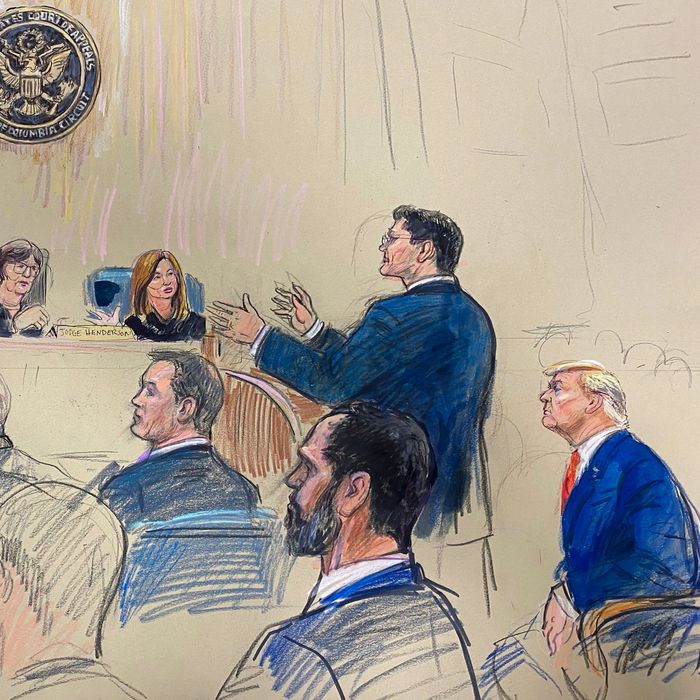

In this courtroom artist’s sketch, Donald Trump listens as his attorney D. John Sauer, standing, speaks before the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Photo: Dana Verkouteren/AP

On a morning when most of the Republican candidates for president were struggling to campaign through snowy Iowa and a poll showed Nikki Haley surging into single-digit territory behind the front-runner in New Hampshire, Donald Trump — the once and quite possibly future president — decided to go to Washington to face the man he seems to consider his only serious opponent: Jack Smith.

There was no reason Trump had to attend Tuesday’s appeals-court hearing on his sweeping claim of presidential immunity from prosecution for his actions leading up to the January 6 insurrection. He had lawyers to make his arguments. There were no cameras trained on him as he sat next to them in the courtroom, mostly quietly, through an hour or so of abstract argument about legal limits on presidential power. Trump was there because he wanted to be in court. The candidate who had squeezed millions of dollars in free airtime out of the media in 2016 just by being horribly exciting, who turned Mar-a-Lago into an alternative White House and the actual White House into the site of the 2020 Republican Convention, is now trying to pull a similar trick with the legal system. The question looming over this year is whether he has finally run into an institution he can’t break.

For now, Trump is treating his prosecution as a dramatic vehicle, once again creating a political show. Knowing Trump would be coming, people began lining up well before dawn outside the E. Barrett Prettyman federal courthouse — not just the usual crowd of reporters but regular folks and interested observers like Trump legal antagonist George Conway. Blue lights flashing, Trump’s motorcade came in through a route protected by a barricade of snowplows and slipped into a secure garage from which he was ushered into the courtroom via a side entrance. Smith, the special counsel who has secured Trump’s indictment in two cases, sat grim-faced behind James Pearce, the government lawyer who would be making his argument. A three-judge panel — two Democratic appointees, one Republican, all women — entered the courtroom, and all rose.

Trump has advanced many arguments for dismissing the January 6 case, one of four prosecutions he currently faces in federal and state courts. His immunity claim is the most ambitious, advancing a doctrine of presidential power that is staggering in scope and sharply at odds with the way most legal scholars understand the Constitution. In a brief filed with the court, Trump’s attorneys cited Marbury v. Madison — the foundational decision establishing the principle of judicial review — to claim that no current or former president “may be criminally prosecuted for his official acts unless he is first impeached and convicted by the Senate.” Because Trump was impeached for inciting insurrection after the U.S. Capitol attack but not convicted, the former president’s team argues he is off the hook.

In a decision issued last month, the judge handling the January 6 case, Tanya Chutkan, dismissed Trump’s immunity claim, noting that the text of the Constitution says an impeached and convicted president cannot be given a punishment by Congress beyond removal from office but “shall nevertheless be liable” to later criminal prosecution. Nothing in the text addresses which actions the state can take against a former president who was acquitted or never impeached at all, but Chutkan concluded that the “limits on impeachment’s penalties do not license a President’s criminal impunity.” She wrote that “no court — or any other branch of government — has ever accepted” that a president is immune from prosecution after leaving office. She noted that several presidents have come close to being indicted in recent history: Gerald Ford pardoned his predecessor, Richard Nixon, to head off a likely prosecution for Watergate-related crimes; Bill Clinton came to a non-prosecution agreement with the independent counsel overseeing the Monica Lewinsky case on his final day in office, in which he admitted to perjury, paid a small fine, and gave up his law license. During Trump’s second impeachment trial, which took place after he left office, Trump’s own lawyers had argued he was no longer subject to conviction by the Senate since he was no longer in office but could be “subject to criminal sanction after his presidency.” Now, Chutkan noted, Trump’s lawyers were arguing that the Senate had missed its chance, contending that Trump now had what amounted to a “lifelong ‘get out of jail free’ pass” for any crimes he committed in office.

During Tuesday’s argument, the three judges on the panel pressed Trump’s lead appellate attorney, D. John Sauer, on the implications of his impeachment-first argument. “Unless there is that one gatekeeping incident that has to occur,” Sauer said, “the court has no jurisdiction.” He brought up Nixon v. Fitzgerald, a nearly 50-year-old precedent that Trump’s case relies heavily upon, which holds that presidents have “absolute immunity” from civil lawsuits for actions taken within the “outer perimeter” of their duties. Similarly long-standing legal opinion within the Justice Department holds that a sitting president is immune from prosecution while in office. (Robert Mueller cited this opinion as a reason for not pursuing Trump on criminal obstruction-of-justice charges connected to Mueller’s investigation into Russian election interference.) Sauer argued that it would “open a Pandora’s box” if the court failed to extend criminal immunity to ex-presidents.

“The current incumbent president is prosecuting his political opponent,” Sauer said, gesturing in the direction of his client, the Republican front-runner. He suggested a future Justice Department or state court might do the same to Joe Biden — a scenario that wasn’t so far-fetched considering the client sitting next to him had threatened to do just that.

Trump has repeatedly forced the American system to reckon with questions that, just a few years earlier, might have sounded like hypotheticals thrown out in law-school bull sessions. Does the Constitution allow a president to run a private business — in fact, to profit from a hotel right down the street from the White House? Can a president be impeached for bullying a foreign leader into helping him smear an opponent? What happens if a defeated president refused to accept the results of an election, telling aides he was simply “not going to leave” (as Trump’s former attorney Jenna Ellis, who has pleaded guilty to a felony charge in Georgia, has reportedly told prosecutors)? Article II of the Constitution requires the president to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” But what can the legal system do if its caretaker turns out to be a crook?

“I think it’s paradoxical,” Judge Karen Henderson told Sauer, “to say that his constitutional duty to take care that the laws be faithfully executed allows him to violate the criminal law.” But Henderson, a Republican appointee who has been amenable to Trump’s arguments in some previous cases, seemed at least willing to consider the possibility that subjecting presidents to criminal prosecution for their actions may have unintended consequences and wondered aloud how it would be possible to write an opinion that “stops the floodgates.” Her two Democratic-appointed colleagues, J. Michelle Childs and Florence Y. Pan, seemed decidedly less sympathetic. Pan posed her own set of hypotheticals to Sauer. Most provocatively, she asked whether an unimpeached president could be tried and convicted for sending assassins to kill an opponent.

“That’s an official act,” Pan said.

“My answer is a qualified yes,” Sauer said, repeating his case that the president could be convicted of murder in a criminal trial if first impeached and convicted in Congress. He added that the Founders were less concerned about criminal presidents than they were about political prosecutions arising from what James Madison described as “new-fangled and artificial treasons.”

“You’re saying a president can send SEAL Team Six to assassinate a political rival,” Pan said.

Sauer replied that “the president’s acts are never examinable by the courts.”

“The president has a unique role, but he is not above the law,” Pearce, the government’s appellate attorney, said as he opened his argument. Even if there might be some theoretical justification for shielding ex-presidents from nuisance prosecutions, he said, this case — involving a plot to overturn an election — was “not the place to recognize some novel form of immunity.”

To the “Pandora’s box” argument, he replied that the lack of previous prosecutions of former presidents “reflects the fundamentally unprecedented nature” of the charged crime. He seized on the “frightening” implications of Sauer’s response to the judge’s hypotheticals.

“That’s not a frightening future; that’s our Republic,” Sauer said in his rebuttal. A Trump trial, he said, “is the frightening future that is tailor-made to launch cycles of retribution.”

After the arguments were over, Trump slipped out of the courtroom, and after he spent another hour or so in the courthouse — presumably, he and his lawyers had much to discuss — his motorcade made its way to the luxury hotel now known as the Trump International. (He sold it to a Miami-based investor group in 2022 for $375 million, likely making a substantial profit.) “We had a very momentous day in terms of what was learned and what they’ve conceded,” Trump said. “I feel that as a president you have to have immunity. Very simple.”

No one else who heard the arguments on Tuesday — least of all the judges — seemed the least bit convinced. Then again, Trump’s strategy is not to win in this court, or maybe even in the Supreme Court, where the conservative majority may give him a more sympathetic hearing. His claims of persecution inflame his base, which he needs to mobilize in Iowa, New Hampshire, and (perhaps) beyond. His outrageous claims keep him on the air, sucking up the oxygen that might feed other candidates and creating spectacle after spectacle. And the longer he litigates, the further he pushes off the date of his potential trial, which is currently scheduled to begin in early March but has remained stayed as he litigates his almost certainly doomed immunity claim. Smith and his team have pleaded for unusual haste from the appeals courts without explicitly stating the self-evident reason for their urgency: If Trump wins the election, there will likely never be a trial. But the legal system has its own pace and procedures. It prizes deliberation. And Trump has shown, time and again, that he knows how to turn a system’s core values to his personal advantage.